How to tell if a graph is a natural monopoly?

Imagine your graph is whispering secrets, like “Psst…I’m basically the economic equivalent of a subway sandwich that’s too long to share.” To decode its monopolistic murmurs, start by eyeing the cost curves. If the average total cost (ATC) line slopes downward like a playground slide made for a single, overly enthusiastic kid (read: one firm) to ride forever, you’re likely dealing with a natural monopoly. The bigger the output, the cheaper it gets—because why share the fun of infrastructure costs when you can hoard them like a dragon with a fiber-optic network?

Does demand play hard-to-get with the ATC curve?

Check if the market demand curve cozy-fies up to the ATC curve while it’s still falling. If demand hugs the ATC like a yeti trying to limbo under a “low barriers to entry” sign, that’s a red flag (or a yeti flag). Natural monopolies thrive when the minimum efficient scale is so massive, it’s like needing a Godzilla-sized factory just to serve three customers. Efficient? No. Economically inevitable? Absolutely.

The “subadditivity” sniff test

- Subawhat-now? Subadditivity means one firm’s total cost is cheaper than splitting production among rivals. Like ordering one pizza for yourself vs. coordinating three group orders that somehow cost $400 and arrive cold.

- If your graph’s cost structure looks like a burrito so large it defies the laws of physics—congrats, it’s subadditive. Breaking it into smaller burritos (firms) would just create chaos, guacamole shortages, and higher prices.

The “LRAC Attack” (Long Run Average Cost)

If the LRAC curve is still throwing a pool party downhill while demand sulks in the shallow end, you’ve got a natural monopoly. It’s the economies of scale equivalent of a “Buy 10,000, Get 10,000 Free” deal. At this point, competition isn’t just tricky—it’s like showing up to a chess match with a spoon. Sure, you could try, but the board’s already tilted in favor of the reigning champion.

Still unsure? Ask the graph: “Would splitting your industry feel like dividing a cookie into crumbs that somehow cost $3 each?” If it nods (or axes your profit margins), natural monopoly confirmed. Now go forth, and may your cost curves forever slope absurdly downward.

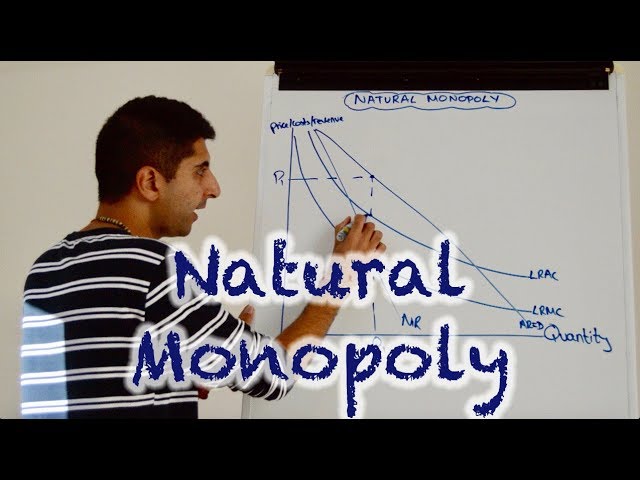

What does a natural monopoly graph show?

It’s the economics equivalent of a “You Had One Job” meme

Picture this: a downward-sloping long-run average cost (LRAC) curve that never, ever stops falling. Like a rollercoaster designed by a mad squirrel, it plunges toward lower costs as output increases, mocking the very idea of competition. This graph is basically screaming, “Hey, look! One massive firm can supply the entire market cheaper than a gaggle of smaller firms!” It’s the kind of efficiency that makes “monopoly” sound almost wholesome—like a hug from a blockchain-powered teddy bear.

Where the magic (and market failure) happens

The graph’s star players include:

- The LRAC curve: A.k.a. the “costs downhill slide” that ruins everyone else’s profit picnic.

- Demand curve: The awkward bystander, often intersecting LRAC where one firm can supply all customers without breaking a sweat.

- Market quantity: Hiding in the corner, quietly accepting its fate as a single giant’s playground.

This isn’t just a graph—it’s a Shakespearean tragedy for free-market enthusiasts. The LRAC curve is addicted to napping at “low costs,” while competitors trip over their own shoelaces trying to enter the market.

Why regulators eye this graph like overcaffeinated detectives

Regulatory agencies see this graph and immediately start sweating. That subway-tunnel-shaped gap between LRAC and demand? It’s the VIP lounge for monopolies. Once a firm claims that space (think utilities, railways, or your local sentient Wi-Fi cloud), competition becomes as practical as teaching llamas to tap dance. Regulators then face a dilemma: let prices plummet to cost (and watch innovation nap forever) or set prices higher (and risk turning the monopoly into a cash-spewing dragon). Either way, the graph sits there, smug and unchanging—a silent reminder that economics is just applied chaos theory.

What is the curve of a natural monopoly?

Picture a unicorn riding a skateboard downhill while juggling flaming economics textbooks. That’s basically the vibe of a natural monopoly’s cost curve. Unlike regular monopolies (which are just bullies with market power), a natural monopoly thrives because its long-run average total cost (LRATC) curve slopes downward forever—or at least until it runs out of customers. This happens when one company can supply the entire market cheaper than two or more rivals, thanks to colossal fixed costs (think: railroads, utilities) that make competition as practical as a chocolate teapot.

The “Why Bother?” Zone of Efficiency

Imagine building a second water supply network for your city. You’d need:

- Enough pipes to wrap around the moon (twice)

- A CEO who’s cool with losing money for decades

- A regulatory agency willing to nod along

This is why natural monopolies exist: their economies of scale are so dramatic, splitting the market would be like hosting a dance-off between grumpy tortoises. One firm’s LRATC curve just keeps dipping as it produces more, making rivals as redundant as a screen door on a submarine.

When One is Enough (Seriously, Stop Trying)

The natural monopoly curve isn’t greedy—it’s efficient. If two firms split the market, both would face higher average costs, leading to a showdown of financial despair. It’s like the universe saying, “Congratulations, you’ve won capitalism! Now please stop. Everyone else has left the party.” Governments often step in to regulate these lonely giants, because unchecked, they’d morph into that friend who insists on controlling the aux cord *and* the thermostat. Forever.

So next time you pay your electricity bill, remember: you’re basically tipping a grumpy, legally-mandated robot that’s mastered the art of cost curves. You’re welcome.

What makes a natural monopoly?

When one giant hamster wheel powers the whole town

Imagine a world where two companies try to supply tap water by building separate, parallel pipe systems under your street. One pipes lemonade, the other melted snow cones. Chaos? Absolutely. That’s the essence of a natural monopoly—where duplication is so gloriously inefficient that everyone quietly agrees, “Let’s just let Larry handle the pipes.” These monopolies emerge when industries require:

- Eye-watering upfront costs (think railroads, utilities, or a chocolate fountain network)

- Economies of scale that make bigger = cheaper (like a single mega-factory producing ALL the bubble wrap)

- Infrastructure that’s harder to replicate than a decent sourdough starter

The “Why Build Two?” principle

Natural monopolies are the overbearing plant parents of the economy: they thrive because competition is *logistically* ridiculous. If your town already has one electrical grid run by a sentient pile of copper wires, why would anyone pour billions into a competing grid that… also does the same thing but with more jazz hands? The math ain’t mathing. Plus, splitting the market would mean higher costs for everyone—like two rival rollercoaster tracks looping through your backyard.

Government: The babysitter of inevitabilities

Since natural monopolies tend to flex their power (see: the time a single gas company tried to charge customers in hugs), governments often step in to say, “Cool infrastructure, but no naps on the job.” Regulation ensures these monopolies don’t go full supervillain—setting fair prices and mandating that your internet provider can’t respond to outages with a shrug emoji. It’s a delicate dance between “efficiency” and “not letting one company own all the clouds.”

In short, natural monopolies exist because sometimes, letting one entity control the spaghetti of pipes, cables, or nuclear confetti factories is just… less insane. Embrace the absurdity!