What did it mean to Duck and Cover?

Picture this: It’s the 1950s, the world is sweating through the Cold War, and someone decides the best way to survive a nuclear explosion is to pretend you’re a tortoise. Enter “Duck and Cover,” the OG of survival hacks—a move so delightfully absurd it makes TikTok challenges look like Shakespearean theater. The premise? If you see a flash brighter than your future, immediately fold yourself into a human origami under the nearest desk, because obviously, laminated wood stops gamma rays. Bonus points if you use a textbook to shield your head. Algebra: saving lives since 1951.

Step 1: Spot the Flash. Step 2: Become Furniture.

- Drop everything (including your dignity).

- Assume the fetal position beneath something flimsy, like a school desk or your neighbor’s questionable life choices.

- Pray that the atomic fireball respects personal space.

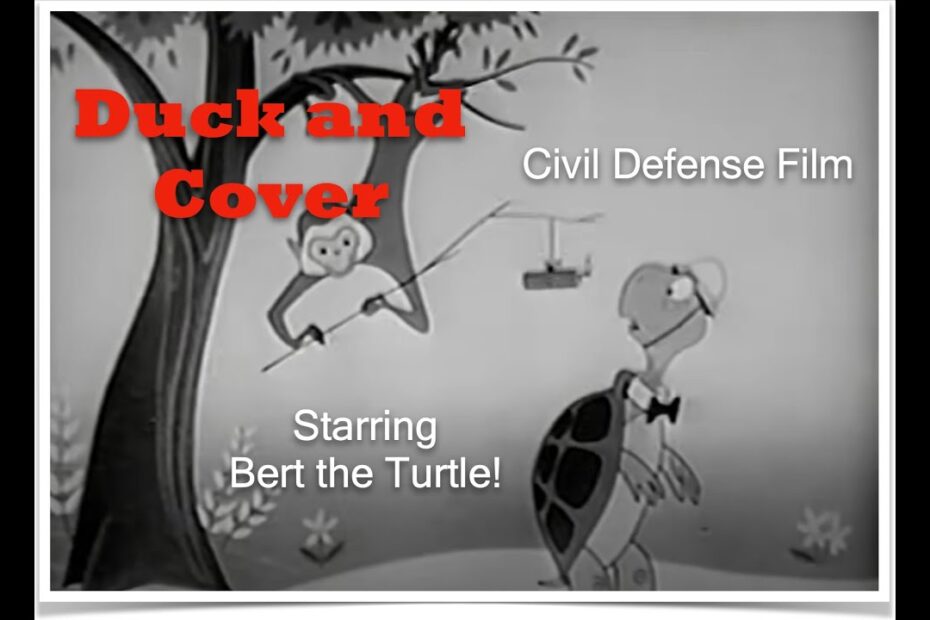

This trifecta of terror was taught via grainy films starring Bert the Turtle, a cartoon reptile with more survival instincts than your average congressman. Bert’s advice? “Duck and Cover!”—a phrase that also doubles as excellent dating app bio material.

Beyond its practical flaws, Duck and Cover became a cultural mood. Imagine practicing air-raid drills between math class and lunch, where the scariest thing wasn’t pop quizzes but pop—ulations disappearing in a mushroom cloud. Schools stocked fallout shelters like they were prepping for a radioactive bake sale, and kids earned “Civil Defense” badges for mastering the art of hugging linoleum. It was an era where optimism and denial did the tango, and everyone got a participation trophy… if they survived.

In hindsight, Duck and Cover was less about safety and more about collective coping via chaos. Sure, your desk wouldn’t stop a blast, but at least you’d die with impeccable posture. The drill’s legacy? A masterclass in gallows humor—proving that even existential dread could be repackaged as a quirky group activity. Just add glitter (or fallout) and call it a party.

What is the Duck and Cover method?

Picture this: It’s the 1950s, the world is sweating over atomic anxieties, and someone decides the best way to survive a nuclear explosion is to imitate a startled turtle. Enter the Duck and Cover method—a civil defense gem that taught generations to “drop like a pancake” at the first sign of apocalyptic glitter (aka a nuclear blast). The technique? Simple. If you see a flash brighter than your future, immediately duck under the nearest desk, table, or existential dread, and cover your head like you’re hiding from your own poor life choices. Bonus points if you practice this with the enthusiasm of a kindergarten nap time.

How to Duck and Cover Like a Pro

- Step 1: Spot the ominous flash (or, alternatively, confuse a camera flash for doom).

- Step 2: Drop to the ground faster than your motivation on a Monday.

- Step 3: Shield your noggin with anything nearby—a textbook, a casserole dish, or sheer denial.

- Step 4: Wait patiently for the all-clear, or until your legs fall asleep, whichever comes first.

This method was popularized by Bert the Turtle, a cartoon reptile with more survival instincts than your average action hero. Bert’s mantra? “Duck and Cover, kids—it’s not just for avoiding chores!” Schools nationwide drilled this routine, blending atomic preparedness with calisthenics. Because nothing says “educational priorities” like teaching children to play human tortoise during science class. Spoiler: The desks weren’t radiation-proof, but hey, at least everyone got a core workout.

Critics argue Duck and Cover was about as effective as using a napkin to stop a tsunami. But let’s be fair—it wasn’t *just* about survival. It was about style. Why face the end of days standing up when you can cower artistically? Plus, it gave the Cold War era its own viral dance craze: “The Atomic Flop.” Just add mushroom clouds and jazz hands. Today, it’s a retro reminder that sometimes, humanity’s best defense against oblivion is… well, a optimistic shrug and a sturdy textbook.

Does Duck and Cover actually work?

Let’s cut to the chase: if your survival plan for a nuclear explosion involves hiding under a desk like a startled armadillo, you might want to rethink your life choices. The iconic “Duck and Cover” drills of the 1950s sold the idea that folding yourself into a human origami project could outsmart a mushroom cloud. Spoiler: it’s about as effective as using a spaghetti strainer to stop a tsunami. But hey, at least you’ll look *fabulously prepared* while vaporizing.

But wait, what if the nuke is… polite?

Proponents argued that ducking could protect you from flying debris (read: the universe’s worst piñata party). Sure, if the bomb detonates *several zip codes away*, maybe your trusty school desk shields you from a rogue stapler. But if it’s within “oh no” distance? That desk becomes kindling, and you become a shadow on the wall. The real threat wasn’t the blast—it was the existential dread of realizing your teacher’s advice ranked somewhere between “eat your vegetables” and “mythical creature safety tips.”

The 3-Step Guide to Surviving Armageddon (Circa 1952):

- 1. Duck: Transform into a human croissant.

- 2. Cover: Use anything nearby—textbooks, existential denial, a hat.

- 3. Pray: To whatever deity invented the concept of “acceptable risk.”

Modern science confirms that Duck and Cover’s greatest achievement was distracting kids from asking harder questions, like “Why does the principal have a fallout shelter but we get a desk?” It’s the survival equivalent of putting a Band-Aid on a volcano. That said, the technique *does* work splendidly for avoiding awkward conversations, surprise birthday parties, or that one coworker who “just wants to brainstorm.” So, is it useful for nuclear Armageddon? No. For everything else? *Duck, cover, and keep the dream alive.*

What was the point of the film Duck and Cover?

Ah, Duck and Cover—the 1951 cinematic masterpiece that taught generations of schoolkids how to defeat atomic bombs with the power of desk-related yoga. The point? To convince children (and their shell-shocked parents) that hiding under a flimsy wooden desk or clutching a newspaper over their heads could somehow outsmart a nuclear apocalypse. Spoiler: It couldn’t. But hey, atomic optimism was all the rage!

Survival tips from the “Age of Anxiety” (and a cartoon turtle)

The film’s real agenda was to package Cold War panic into a digestible, slightly surreal PSA. Enter Bert the Turtle, the animated mascot of existential dread, who taught kids to “duck and cover” like it was a fun playground game—not a last-ditch effort to avoid being vaporized. Key takeaways included:

- School desks: Nature’s neutron bomb deflectors (according to someone who’d clearly never seen a mushroom cloud).

- Newspapers: Not just for fake news! Also a great way to shield your face from radioactive fallout. Maybe.

- Blind faith in authority: If Bert says you’ll survive, who are you to question a turtle in a government-issue raincoat?

It wasn’t about safety—it was about *vibes*

Let’s be real: The film’s creators knew a desk wouldn’t save anyone. The actual point was to give the illusion of control during an era when suburban backyards doubled as bomb-shelter showrooms. By turning nuclear annihilation into a quirky classroom drill, they transformed unimaginable horror into something almost… wholesome? Think of it as Pinterest-worthy preparedness for the “duck and cover” generation.

In hindsight, the film is equal parts dark comedy and time capsule—a reminder that sometimes, humanity’s response to impending doom is to shrug, slap on a cheerful jingle, and hope the blast radius respects your cursive handwriting practice. Duck first, ask questions later.